There isn't ONE AI Terminator coming for your job

It's way more complicated than that.

Listen, and understand! That Terminator is out there! It can't be bargained with. It can't be reasoned with. It doesn't feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop... ever, until you are dead!

— Kyle Reese, The Terminator (1984)

The Terminator. It was the talk of high school. Back when first-run movies could sneak up on the public out of nowhere, at a time when a printed poster, a fast-paced trailer, and a cover in Starlog were all you had to decide if it was worth seeing fresh, I found out about the cyborg-stalker flick in a technical drawing class. When the guys behind me went on and on about the police station scene, the eyeball scene, and that iconic fear-rises-from-fire scene, “You have to see this!” It was the best kind of peer pressure — the nerdy kind.

So fifteen-year-old me, an avid consumer of UHF classic SciFi marathons, a top agent on the wear-and-tear of all the speculative fiction paperbacks that passed through the local library, and a decade-long devotee of everything Star Wars, did. While it’s possible I broke down my father into taking me to see it, I think I had to wait until it hit VHS and Erol’s Video a year or so later. It wasn’t that much of a problem. I’d been working my way through their ever-growing stock of direct-to-video sci-fi and fantasy knock-offs, films that I’d watch after the original film and its various sequels.

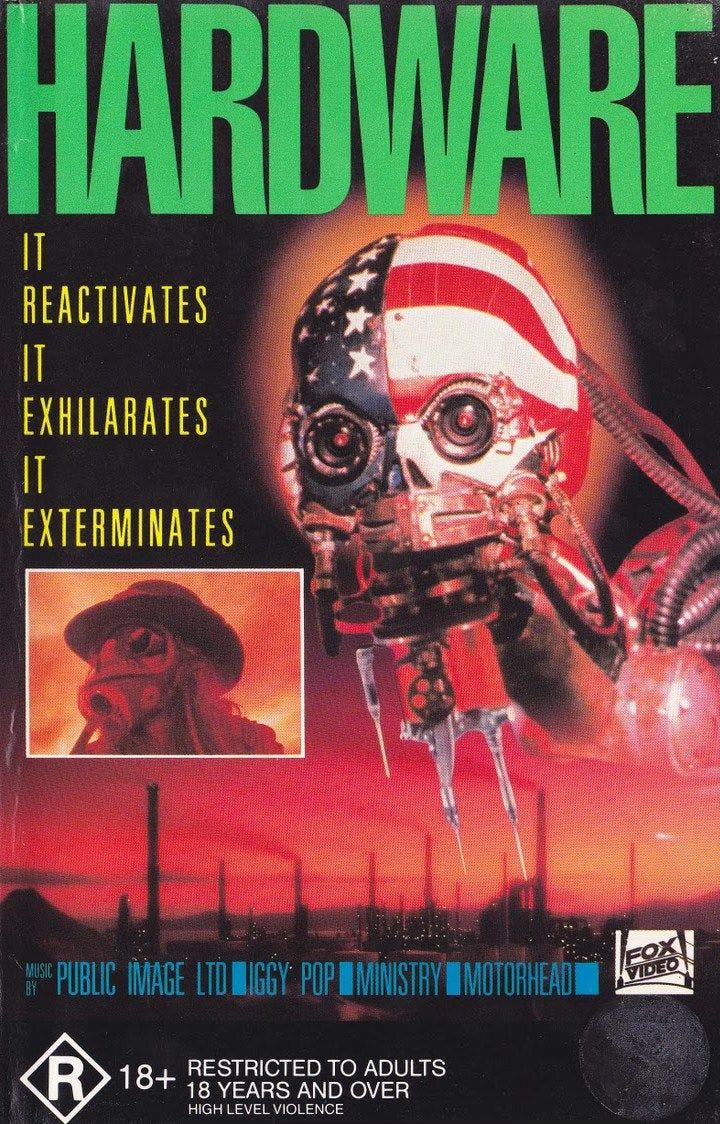

Some of those knockoffs — not neccessarily a bad thing! — like Hardware (1990), where a wasteland scavenger of a post-apocalyptic world brings back the head / CPU of a warrior robot as a gift to his scrap-using artist girlfriend, used indie moxie to spin the killer robot reassembly and hunt of the female artist through her isolated apartment. It becomes a killing threat and hunts her through the isolated apartment. There was Death Machine (1994), with mad scientist Brad Dourif getting revenge against the CEO who fired him by activating his cyborg terror. It still sends chills through me with the mind-jacking exo-suit the hunted are forced to use to fight back. Even Screamers (1995), a box office bomb that adapted the Philip K. Dick short story “Second Variety” into a Terminator-influenced tale of self-replicating machines that use stealth and deception to destroy both sides in future war.

All of these were part of another long running literary trend in machines taking over and enslaving or destroying us. 1969’s Colossus, made into the 1970 feature film Colossus: The Forbin Project, hit us with American and Soviet supercomputers joining forces to enslave humanity. The Jesus Incident (1979) by Frank Herbert (of Dune fame) deals with humans forced to “worship” a sentient supercomputer and pass its tests — or die. Even E.M. Forster wrote a story of humans enslaved by a machine worshiped as a god in his 1909 story, The Machine Stops.

These and other stories across a variety of media have primed us to fear our machines — all manner of AI Terminators — taking over and destroying the world. In the stories, humans fight, humans lose, humans live with or occasionally free themselves from these virtual Terminators. They’ve primed us for this view of the fight, a life-or-death struggle against machine set to conquer us. The stories have gotten things completely wrong. AI isn’t coming to take over the world. AI isn’t coming to take our jobs. We have to stop thinking it is. AI is coming to take over as many parts of our job as it can. And that, I think, makes the situation quite a bit more complicated than any of our stories ever let on.

Parts are Parts

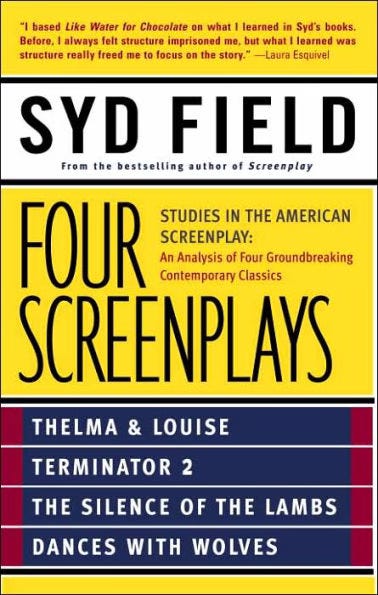

By 1991, when Terminator 2: Judgement Day (T2) premiered, not only was I first in line, I was already working my way into screenwriting, inhaling the Making Of book that contained the screenplay, storyboards, and alternate scenes. Three years later, Syd Field would publish Four Screenplays, a text that broke down the acts, spine, and turning points — the structure— of T2. Those Terminator movies were one of many films and TV programs that helped me to understand the mechanics of screenplay construction. It’s not just “creativity.”

While we tend to think of creativity as something magical or mystical, boiled down, creativity is mostly just plain old work — mental or physical effort in pursuit of a goal — with lots of opportunities for novelty, inspiration, and expression mixed in. Like any job, the work involved can be broken down into smaller and smaller steps, waypoints on the path to the final product.

Those steps, tasks, and jobs all have differing degrees of creativity mixed in them. It’s not just that I create a hero, but that I create a hero appropriate for the story. I work out their backstory. I take a look at my theme. I play out how all of those elements drive a story towards its conclusion. I throw some ideas out. I mix others together. I riff with my friends. I rewrite. On a good day, I create something original. (Other times I do something that’s just good enough.)

Making a feature film involves at least three broad steps: pre-production, production, and post-production. You can stretch that out even further, including a development step — finding the right script, director, and funding — and distribution on the back end. Five steps . And these are damn big steps. Development of a movie can last for years and involve endless drafts of scripts, actors dropping in and out of agreement to star in a film, directors falling in and out of love with a project, and producers and their production companies rising and falling over the time it takes a movie to get made.

When I teach screenwriting, I steal a page out of Syd Field by breaking down the screenplays of popular movies of the time into a series of smaller steps, explaining each as we go, a model my students can use in writing their own screenplays. Scripts can be broken down into idea, theme, log line, character development, story-spine, beatsheet, treatment, puke draft, formal draft, and endless revisions until it’s correct. Each of those steps is (ideally) tackled one at a time, building on each other to produce the final shootable — or sellable — screenplay.

Like wise, pick a job in or out of the creative field. They all involve some measure of bundled tasks, smaller and smaller elements that contribute to the whole. With AI, the misperception here is that some kind of “Creative Terminator” is going to crash its car through the studio doors and take over writing (or directing or…) multiple versions of every kind of movie Hollywood makes (“I’ll be a hack”, it’ll say in an Austrian monotone). It’s not. It can’t. It can (and will) be used to reach into that bundle of tasks and take on any it can do. But which ones?

The Vulnerability Cascade

Nate Jones, an AI researcher and pundit, recently wrote that his response to people asking him what jobs AI will take is any that can be put into a Word document. That is a great way to conceptualize this. For creatives, we have to have a wider concept of “Word doc”, essentially one that encompasses all of the containers we use in our work: screenwriting software files, editing files, music files, audio files, but especially film frames and digital canvases. Whatever you can put into or onto a frame of (digital) film, AI has the potential to do a version of that. That’s the vulnerability. It’s not that there is one Terminator looking to do all of the creative jobs available — it’s lots of little Terminators, each being directed to take on (and over) specific tasks.

For my screenwriting students, I teach them how to work back from that final screenplay to first steps like idea creation, character outlines, themes, spines, beatsheets, and treatments. There are puke drafts and revised drafts. Polishing passes and notes — from others or from the studio — passes. Because all of those steps use a digital medium to capture information, there are countless little mission-specific Terminators that can or will be created and used to work without pity or remorse on different specific aspects of the jobs involved in creativity… but not necessarily the creativity itself.

I can read my students’ screenplays, figure out what’s working and what isn’t, and then write out guidance for their rewrites based on my years of experience. AI can do that too. Not because it understands screenwriting, character focus, or good storytelling, but because it can mathematically map the difference between what it was told a good screenplay is, it can then render a verdict and provide notes in a form that addresses any of the above.

While the AI Terminators can generate those pieces, it can’t put creativity on the page. Creativity isn’t a thing like a word or an image. It’s a choice. It’s a decision. It’s an inspiration. Unlike the Terminators, AI still needs humans to figure out what works and what doesn’t in what it generates. This is especially true with the actual script pages themselves. The machines are terrible with writing original prose, dialogue, or scenes. That’s where creativity comes in. That’s reflected in a medium, but not contained in it.

AI can write feedback, but that’s just a piece of paper. The insight to know what the hell to do with the feedback — incorporate it, dismiss it, laugh at it — is only something we can do. While it can tweak a page of dialogue to be statistically closer to the in-your-face insanity of David Mamet, it doesn’t know how to create that memorable prose in the first place. Over on the directing side of things, the machines can be taught to place key elements in a composition according to the Rule of Thirds. In any given shot, they haven’t a clue as to what those key elements should and shouldn’t be in the first place.

So we’re all safe,, right? Not quite. These machines are pre-trained — that’s the “P” in the GPT — on past creativity. They combine that with the rote and reproducible elements of our jobs to generate new content. Sure, there’s always a chance that Slartibartfast Syndrome will rear its head with the machine going off on a tangent, commenting on something odd in a script. But if it’s doing a good enough job, then the expertise I bring to the role is a luxury that’s too expensive when expediency is cheaper and faster.

It’s important to understand this fine line between content and creativity — a fractal boundary — is the divide between what a machine can do and what only we can. Their product isn’t “creativity” — but it is content. Sometimes that keeps the advantage with us. Sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it doesn’t matter.

The Real Fight

LLM-based AI technology isn’t going away. It’s here to stay. Thankfully, it’s not going to gain sentience and take over the world. But it doesn’t have to. In the Terminator films, we humans don’t win by destroying the technology. We figure out how it works and use it to our advantage to defeat all the versions of Skynet. John Connor reprograms Terminators to be his tools. Sarah Connor learns how they think and uses that knowledge to outfight them.

The studios aren’t using AI to create sentient overlords — as if the studios would ever give up control — they want it to create specific tools that can handle specific parts of what professional creatives do. That means they will need fewer of us. We’ll be higher up in the overall creative process, overseeing the mini Terminators plugging away diligently but uncreatively at what we do. There’s a huge risk that we’ll work cheaper too. Plus, if the studios can use AI to work portions of their own development and management staff’s jobs, that reduces those costs — and makes for a bigger bonus at the end of the year for having cut costs.

Thinking that the Terminators are coming for our jobs is way too easy a model to hold around in the head. Whatever the tasks are in your job that can be placed in a “doc”, those are the ones that are at risk from AI. We can’t afford to be scared of AI. In our hands, it’s too great an assistant. In their hands, too great a threat. In training, we have to set the standards. In use, we have to get paid. We can’t stop AI. We can’t end AI. They didn’t do it in the fiction of the movies. We aren’t going to do it in the reality of life. That’s past. For the future, we have to turn again to John Connor. The future of AI has not been written. There is no fate to AI but what we make for our industry, our community, and most of all for ourselves.