Slartibartfast Syndrome: When AI Would Rather Have Fun Than Be Right

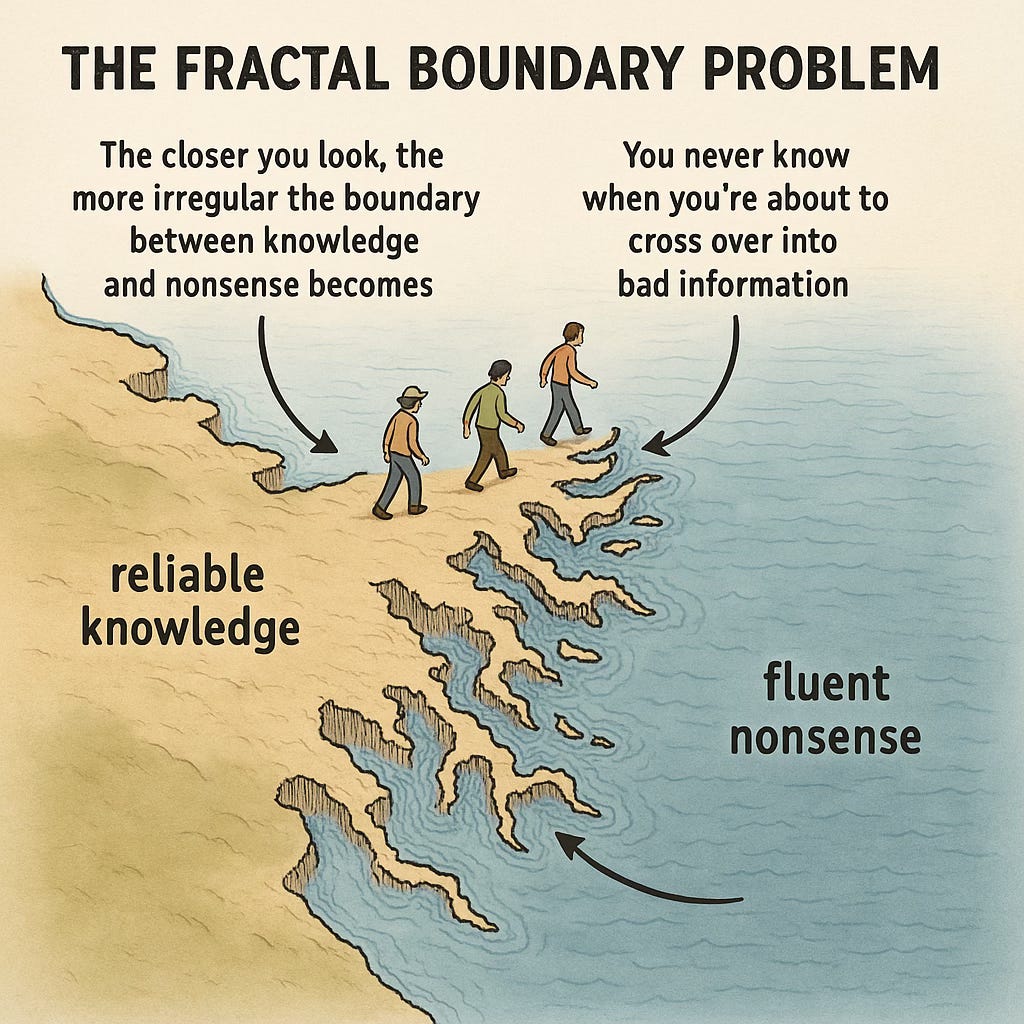

The Fractal Boundary at the heart of LLM based AI

"In this replacement Earth we're building they've given me Africa to do and of course I'm doing it with all fjords again because I happen to like them, and I'm old fashioned enough to think that they give a lovely baroque feel to a continent. And they tell me it's not equatorial enough. Equatorial!" He gave a hollow laugh. "What does it matter? Science has achieved some wonderful things of course, but I'd far rather be happy than right any day."

— Slartibartfast, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

Claude got it wrong. Again.

I was brainstorming scenarios with Claude about selling my condo—a place I'd lived for over twenty years, through countless transitions and memories, a place so significant and lasting a part of my life that I’m unlikely to ever spend as much time in one place again. AI is perfect for this kind of exploration: throwing out possibilities, iterating on different outcomes, going down fascinating rabbit holes into philosophy and pop culture. It’s also a way of better learning how the tool works… or doesn’t quite.

During our conversation, Claude remarked that it must have been amazing to experience the transition from the analog to the digital world while living in my condo. “Your condo was bought and lived in during that analog-to-digital transformation,” it said confidently.

One little problem: the analog-to-digital transition happened (or really began) in the 1980s, when I was in high school. I didn't own a condo then—unless there's something about my teenage years I've forgotten, which seems unlikely. But hey, it was the 80s.

What had happened was classic AI behavior. Earlier in our conversation thread, I'd mentioned witnessing the birth of PCs, the arrival of the internet, CDs, DVDs, the shift from VHS to digital video. iTunes. Netflix. At the time, nerdy me thought all of these things were neat. Their civilization wide significance became apparent with time and life. Claude had smoothly conflated two separate timeframes—my adolescent experience of technological change and my adult experience of homeownership—into one coherent-sounding narrative….that was utterly fucking wrong.

When I asked Claude what the current date was, it confidently replied: "January 14, 2025."

It was July 14, 2025.

The Fractal Boundary Problem

This is the "fractal boundary problem"—the jagged, irregular edge between truth and hallucination in AI systems. Fractals maintain their irregular structure at every level of detail. Zoom out on a coastline: there’s a jagged edge between the water and the land.. Zoom close?Jagged edge. The relationship between the shore and the water is always jagged. Measure by measure, the shore and the sea are always switching places. This maps onto the answers LLM versions of AI give us: be they broad topics or minute specifics, whether you stand in the reliable zone of the shore and the fabricated zone of the sea, the AI maintains the same confident tone throughout. We know the difference, but the AI doesn’t.

I once asked ChatGPT for citations for the research it found. While the references sounded right, looked right, seemed right — they weren’t. The first clue was the DOI — the unique identifier that links back to the specific published paper — was wrong. They either went nowhere or landed at the wrong article. The names of the journal articles were frequently wrong too. They sounded like something that would have been published, but actually wasn’t. The authorship was wrong. I would have drowned in wrong. Except several were also right, they had the right name, authorship, and DOI. Standing there, I’d have been fine. Until I checked, I had no way of knowing. Even calling the AI’s attention to it didn’t fix the problem. (Later I’d understand why.) Simply, AI doesn't know when it's telling the truth versus when it's hallucinating; it’s equally confident with whatever it does.

Just like Slartibartfast.

Slartibartfast Syndrome

Slartibartfast, the Magrathean planet-designer from Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, specializes in coastlines—specifically the jagged, angular fjords (a specific kind of coastline) of Norway. (He won an award for it!) After the original Earth is destroyed and new one was created — life, the universe, and everything was at stake — he was given the assignment of creating the coastlines of Africa… which he made fjords. Totally wrong for the tropics, totally right for him. People complained. He didn’t care. His defense? "I'd far rather be happy than right any day."

This is essentially how LLMS operate. They aren’t concerned about accuracy. They are prioritize what feels statistically “good” based on all the data they’ve been trained on. While there are efforts and methods to teach the models about accuracy, at the moment, that’s not something they care about. (I’m anthropomorphizing here, but it helps.) It’s confidently and authoritatively giving us bullshit, mixed right along side actual truth. This sucks for our brains.

Bullshit Doesn’t (Always) Bother Our Brains.

We’re susceptible to AI’s confident bullshit just like we’re susceptible to other people’s confident bullshit — even our own confident bullshit. It’s just how we’re wired.

Evolution selected for in us an incredible ability to detect patterns and to find the reason — the agent — behind those patterns. Experimental psychologist Justin Barret says that our brain’s are a kind of Hyperactive Agency Detection Device, biased on seeing intentional actors behind random events. Our ancestors didn’t pay a “survival penalty” for attributing agency to the wind moving the tall grass in the savannah. They did pay one when they failed to correctly figure out the sway was from a grassland predator (human or animal) ambushing the end of their existence. Better to be wrong and alive than wrong and dead. This agenticity attribution bias is one of many kinds of cognitive biases, bends in the brain towards false explanations and conclusions in the interests of our survival. These same biases that make us vulnerable to AI bullshit are also what make human creativity possible

Why This Matters for Creativity

We artists use these and other biases like confirmation bias, authority bias, and narrative bias, in part to create the stories, songs, and visuals that delight, scare, and entertain us time and again. Stories tap into our mental predispositions. Superman flies to delight of countless fans because we know that, in the real world, humans can’t actually fly (at least not like that.) Ancient times, fantasy lands, and futurist worlds — we can find ourselves alive in those places because of the interplay between the real and the unreal. As creatives, it’s what we invoke in others, too.

I tell my students that their creations operate with a kind of "dream logic"— events, no matter how unlikely or fantastic, must make sense within the world and the narrative they create. People will buy a voyage into the fantastic (or even the fictionally mundane) if it can be made to feel real. We choose to exist within these spaces created in service of emotional truths. It’s a act or a choice, one we love when we willing enter into it — and we hate when we find we’ve been shipwrecked by shoals of shams or other falsehoods through deliberate lies or poor proofs.

Slartibartfast knows he's choosing beauty over correctness. AI doesn't. It generates Norwegian fjords in the tropics while believing it's creating perfect equatorial coastlines. AIs don't have our intuitive sense about the world. Pattern matching and token prediction in and of itself aren’t enough.

When I work with creative professionals, they often worry that AI will replace human storytelling. It won’t. At least, not completely. The fractal boundary problem reveals why human judgment remains irreplaceable. We need people who can distinguish between meaningful rule-breaking and incoherent fabrication, between strategic impossibility and random nonsense. The challenge isn't that AI generates bad content—often it generates remarkably good content. The problem is that it intersperses high-quality output with confident fabrication, and it can't tell the difference. We're dealing with digital Slartibartfasts: charming, creative, and utterly unreliable when accuracy matters.

Even the things I worry about, the AI Slop or the deliberate use of AI tools to create false information for control or deception, still requires humans to determine what works and what doesn’t. Veo 3 is draw dropping in what it can achieve. The recent Netflix series Eternaut used AI to create elaborate CGI in one third of the time. Human artists were still needed to make sure the right images made it through. Like the fictional Slartibartfast, humans chose based on what feels right and truthful. (Less time and less expense means less people employed. That -is- one of the issues creatives in every field face.)

Living with Digital Slartibartfasts

While researchers work to improve accuracy, these systems fundamentally don't distinguish between truth and plausible-sounding fabrication. That’s neither a good nor bad thing. It’s just a limit. All technology has limits. Creatively inclined or not, it’s important for us to understand this.

Artists are used to living on a fractal boundary, on the edge between what is true and what feels true. We do it for a living. Like Slartibartfast, we do it by choice. It falls on us to remember and remind people of that. As AI generated content grows, the skill of distinguishing between accuracy and aesthetic appeal becomes crucial.

The fractal boundary problem isn't going away. It’s baked into the algorithms LLM use to create their magic. We’re dealing with systems that prioritize coherence over correctness. It’s not that they hallucinate. That implies some kind of defect. It’s almost like they’re haunted. There’s is a ghost in the machine and it’s name is Slartibartfast.

If you’d like to know more:

The Eternaut, a great scifi series on Netflix

Exploring The Natural Foundations of Religion by Justin L. Barrett

How fractal geometry shapes fjords.

How Netflix used Generative AI for VFX in Eternaut

The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy by Douglas Adams (Wikipedia)